Reeves said, but ignoring the role of the upper middle class “gets in the way of an honest conversation about what’s happening with American inequality.The World’s Growing Middle Class (2020–2030) It’s driven by millions of upper-middle-class families with enough income to foot those bills, Mr. The spread of $3,000-a-month apartments or a national average $32,000-a-year college tuition bill is not driven by heirs or CEOs renting dozens of apartments or sending dozens of children to college. Take high housing costs or the soaring costs of higher education. Reeves argues that many of the social anxieties and resentments against inequality are in fact driven by what he calls “the dangerous separation” between middle- and upper-middle-income families. Richard Reeves, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a centrist think tank, is writing a book called “Dream Hoarders” that looks at the way upper-middle-class families perpetuate their status across generations, in ways that can sometimes be harmful to middle- or lower-middle-class families. (In 160 of the cities, the share of lower-income families grew as well.) So Pew found the middle class shrinking from both ends-not just from families falling below the middle class, but also because of families rising out.

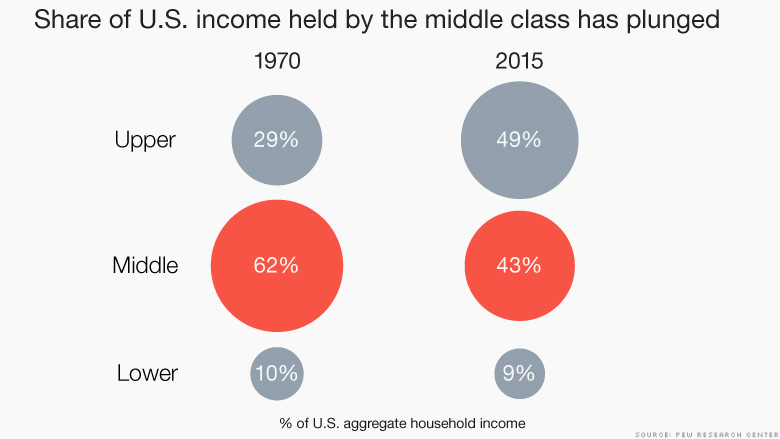

The Pew Research Center last month found that 203 metropolitan areas have seen their middle class shrink, but in 172 of those cities, the shrinkage was in part due to the growth in wealthier families. They define these neighborhoods as those where the median income is at least 50% higher than the rest of the city. Research from Sean Reardon of Stanford University and Kendra Bischoff of Cornell University, for example, found in research published in March that the number of families living in affluent neighborhoods has more than doubled, to 16% of the population in 2012 from 7% in 1980. It suggests that the majority of Americans have indeed struggled but that a large minority has thrived. While it underscores the growth of American economic inequality, it undermines the idea of lower- and upper-middle-class voters being in the same boat. This reappraisal does not fit comfortably in the left or the right’s political narratives. Rose’s new paper is part of a broader body of research reappraising and seeking to measure the upper middle class. But using different measures of inflation, or using higher income thresholds for the upper-middle class, produces the same result: substantial growth among this group since the 1970s. One could quibble with his exact thresholds or with the adjustment that he uses for inflation. Rose adjusts these thresholds for inflation back to 1979 and finds the population earning this much money has never been so large. Smaller households can earn somewhat less to be classified as upper middle-class larger households need to earn somewhat more.

Instead of inheritors of dynastic wealth or the chief executives of large companies, they are likely middle-managers or professionals in business, law or medicine with bachelors and especially advanced degrees. At the same time, they are quite distinct from the richest households. median household income and about five times the poverty level. Using Census Bureau data available through 2014, he defines the upper middle class as any household earning $100,000 to $350,000 for a family of three: at least double the U.S. Rose, by contrast, uses a more dynamic method similar to how researchers calculate the poverty rate, which allows for growth or shrinkage over time, and adjusts for family size. Many researchers have defined the group as households or families with incomes in the top 20%, excluding the top 1% or 2%. There is no standard definition of the upper middle class.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)